Watermarks: Boatmen's Testimonies

2024-2025 | creative writing | hybrid | documentary poetry

In this collection, I give voice to the Qiantang River’s boatmen through a hybrid of ethnographic field notes and lyrical poetry. Inspired by Don Mee Choi’s DMZ Colony, I curated a chapbook that weaves original poems with interview transcripts, translations from my grandpa’s river poems, translations of boatmen’s folk songs, and archival incident reports—documenting a vanishing way of life along Hangzhou’s waterways, where river currents shape human fates and history resurfaces in fragments of song, silence, and record.

Click photo to view the PDF version

Read web version below :)

the waist of a city

117°37' to 121°52' east

28°10' to 30°48' north.

They say the river remembers. Long before

it wore the name Qiántáng, it was Zhè—a syllable bent like its own course, twisting silver

through cliffs and flooded plains. The ancients knew it

as Zhé Jiāng, the Crooked River; as Zhī Jiāng, River of the Bend;

as Luóchà Jiāng, Demon’s River—a name hissed from scrolls

by cartographers who’d seen its fury.

In the south, where mist clings to bamboo groves,

it softens. Here, they call it Fùchūn Jiāng, River of Prosperous Spring,

carrying the scent of tea hills through Fuyang’s dreams.

But when its currents slide toward Hangzhou,

the river gathers itself. Ancient stones line its banks—

whispering of ferrymen, drowned temples, salt-stained sails.

Here, it remembers its true name: Qiántáng.

The river that carved kingdoms.

Where Wú and Yuè kings dipped bronze swords into its waters,

where silt built temples, and tides wrote history.

The river that defies the sea.

Twice each day, the ocean rages back—

a thunderous wall of water roaring up its throat.

They call it the Great Tide, the Dragon’s Breath,

born where the moon’s pull cracks against earth’s spin,

and Hangzhou Bay’s funneled jaws force chaos into form.

Centuries flow. Dynasties name provinces in its honor.

Mountains feed it; cities drink from it; Every bend, every ghost,

every name it ever carried.

随潮发舟

烟雨钱塘潮涌浪,

百舟争上势脱缰。

扶摇直上天际处,

唯留空旷水茫茫。

一九九三年十二月

Setting Sail with the Tide

Rain and mist surge alongside the Qiantang tide,

Boats burst free, like wild horses jostling

They shoot up towards the low, grey belly of the clouds

What’s left, miles and miles of empty water.

(December, 1952)

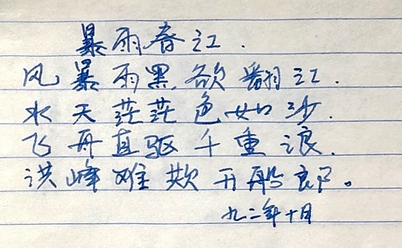

暴雨春江

风暴雨黑欲翻江,

水天茫茫色如沙。

飞舟直驱千重浪,

洪峰难欺开船郎。

九二年十月

Storm on the Spring River

Wind tears dark, turns the river

water and the sky blur, into one pale, sand-like hue.

Boats cut through a thousand crests—

what storms can break who holds the ore?

(October, 1992)

事故 // INCIDENT [1]

After Layli Long Soldier

INCIDENT. From incidere. A word

of falling into–to cut, to trespass, to bleed.

In law, attaching to. In body, detaching from.

INCIDENT: the broom-handle jabbing the gut

into shards of glass, lodged where spine meets air.

Winter breath stabbing nostrils, sharp as the t

capping incident: that final huff, the icicle of a joke

snapping. Lips tightening. Tongue clicking teeth.

In place of incident, teachers explain it as:

A blank space where the body was.

The sound of a rib cracking. (See: DANGER.)

The moss growing inside throats. (See: GUILT.)

INCIDENT(S). Plural. Reefs harboring boats

long-since wrecked, split open. Groaning wood. Wood

filling with water. Dirt. Glass becoming seaglass. No–

they are rifts. Lacerations. Wounds pried wide to hold

everything politicians leave unsaid.

INCIDENT: the soldier who knows blood like his daughter’s

braid, knows fire like his mother’s stove. As the tide

recedes, he lines the bodies neat, legal margins along the ditches.

RECOGNITION: He lies, believing he doesn’t

recognize the faces once he wipes the mud from their cheeks.

--

[1] Note: The title of this poem, shìgù, means incident in Mandarin. The translation of individual characters are: 事 shì–event. 故 gù–cause. 事故 reversed is 故事, which means story.

[2] Official records note. Fragments. Zhejiang, 1954-1983.

1954.5.3 — Chén Yuánqīng (陈元青)’s timber raft capsized in floodwaters at Shíguǒjiāng.

1961.6.3 — Fāng Měidì (方美弟) drowned steering grain barge through Qīngwān Rapids.

1974.8.20 — Unlicensed passenger boat overturned near Baiyán. 4 dead. Captain Wú (吴).

1975.6.19 — Hu (胡)’s overloaded vessel struck reefs at Táohuā Shallows. Lǐ Xīngnán (李星南)—Yúnhé town’s Hydrology Director—among lost.

1983.3.4 — Wú Sōngchéng (吴松成)’s freighter sank at Tānkēng Reef. 24 aboard. 5 fatalities.

[...]

The Ferryman’s Son: Yuanpu Archives

For Li of Yuanpu Town’s Wujia Dock

I. Water Memory

I am the son of the ferryman. The river is my father’s father. Three rivers—Qiantang, Fuchun, Puyang—three threads braided into one rope around our necks… We lived in the knot…

Before the bridges, the world was water.

To go to Xiaoshan for work, you pay my father a coin. Step into the belly of his wooden boat.

When I was a child, my hands learned the shape of the oar

before they learned a pen. The rhythm: dip, pull, creak.

Then men from the city came with their blueprints. They drew lines

across the water. Concrete. Steel. The language of progress. The ferry fell

silent. My father laid down his bone. He returned to the dirt, to speak the slow language of seeds.

The bridge was not a bridge. It was a suture. It stitched

our isolation shut, and we bled a different way.

II. Sand Years

ACT I: THE FEVER

… Everywhere, the cranes… A forest of metal birds… The city eating the village...

The river, they said… held the bones of the city. Sand.

I became a pilot of substance… My barge…

a mountain of sediment… I carried the pulverized past…

to the mouths of the future… Hangzhou… Shanghai… Jiangsu…

The money was a thick, brown current… We were all drunk on it.

ACT II: THE HANGOVER

The government memo, a sudden winter:

Directive on the Rational Exploitation of Riverine Sand Resources.

The river was scraped clean.

The golden goose, gutted.

The fever broke, leaving only the chill.

The mountain on my barge grew smaller,

then vanished.

III. The State’s Vessel & its Ejection

I joined the fleet at Wulinmen. A uniform.

A number. A fixed route: Jiande—Huzhou.

The state’s boat. Lighter work. A smaller current of money,

but predictable.

But a new velocity was being born:

high-speed rail, expressways. They sold time, and we had only space to offer.

The passengers evaporated.

A letter from the company. Route Optimization. Streamlining.

At fifty-six, your services are no longer required.

I was a piece of driftwood washed ashore.

IV. The Apparatus of The Shore // Pension as Interpellation

FIFTEEN YEARS. This is the magic number.

The border between a body that is useful and a body that is allowed to rest.

My timeline is insufficient. My contributions to the collective fund, a thin stream.

Q: Have you EVER been a member of a state-owned enterprise for a continuous period of fifteen years?

A: (No)

Q: Do you understand that your benefits are contingent upon your continuous contribution to the national social security fund?

A: (Yes)

Q: Will you change your employment status?

A: I am fifty-eight. Who will have me?

They say the next town over, the policy is a kinder river. Their government throws a life ring to men like me.

Here in Yuanpu, the policy is a concrete bank. You cannot climb it.

So I have built my own raft. A small shop.

Wushan Ferry: I sell Coca-Cola, instant noodles, single-serving dreams. The coins I collect are not currency. They are tokens for the gatekeeper. Two more years of tokens.

In 2027, I will be sixty. The gate will open.

I will cross from Labor to Rest.

This is the last ferry I will ever take.

—

[1] Yuanpu袁浦—a town located in the southwestern part of Xihu District, Hangzhou City.

[2] In 1998, 浙江省钱塘江管理条例 (Regulations on the Administration of the Qiantang River in Zhejiang Province) was implemented, marking the entry of sand mining in the Qiantang River into a new stage of standardized management.

[3] Wulinmen武林门—an important northern city gate in Hangzhou’s history. First built during the Sui dynasty (around 589 AD).

[4] Article 16 of 中华人民共和国社会保险法 (The Social Insurance Law of the People’s Republic of China): To receive a basic pension, an individual must have reached the statutory retirement age and have made contributions for a cumulative period of fifteen years.

Translation of a Fisherman

I. The Ferrymen’s Son (A False Start)

我父亲是个渔夫。

My father was a fisherman.

他的父亲也是。

His father too.

钱塘江是我们的家。

The Qiantang was our field.

我们继承了一条木船。一张证。

We inherited a wooden boat. A license.

潮汐的节奏。

The rhythm of the tide.

(This is not how it begins. This is the story they expect. Start with the water.)

II. Official Transmission // 钱塘江渔业资源管理通告

Zhejiang Provincial Notice 2019

RE: Seasonal Fishing Moratorium

Article 1: To protect the sustainable development of fishery resources and the ecological environment of the Qiantang River...

Article 2: The annual closed season shall be from 00:00 hours on March 1st to 24:00 hours on June 30th.

Article 3: All productive fishing activities are prohibited during this period. Recreational fishing is permitted.

Definition of “Productive”: Any activity aimed at obtaining aquatic products for sale or trade.

Definition of “Recreational”: Any activity aimed at leisure, entertainment, with a limited number of hooks.

我的翻译 (My Translation): For four months, your hands must be still. Your hunger is not “Recreational.” Your history is not “Recreational.” The river is closed for repairs. You are a malfunction.

III. The Sand Years: A Dream in Two Parts

Part A: The Fever Dream

I piloted a mountain of sand.

The real estate dream.

We fed the city’s hunger.

Fuyang to Shanghai.

Huzhou.

The river was a highway of grit.

I was not a fisherman.

I was a courier of dust.

Part B: The Hangover

The dream ended.

The mountain grew smaller.

The voyages longer (10 days, 20 days).

The pay, a shrinking number.

I slept in a bunk, not a bed.

I was a ghost on a concrete sea.

My father's river called me home, a faint signal.

IV. Apparatus of the Shore (Present Tense)

I came back.

Now, I am a driver for an app.

I ferry people, not fish. I navigate by algorithm—

the city’s arteries, not the river’s veins.

But. My body

remembers the river’s tilt. My hands

remember the weight of a wet net.

So.

Sometimes, I return to the bank. To my small boat.

I lower the cages (shrimp, crab).

This is not ‘Productive.’

This is 'Recreational.'

This is a language only the river and I understand.

A habit.

The catch is small. I sell it to a restaurant by the water.

This is not “Trade.”

This is “Memory.”

My ritual.

V. Notes for a Future Archivist

-

The pollution has a color, but no one can agree on its name.

-

The dams have a purpose: power. The fish have a purpose: to return. These purposes are at war.

-

My license is in a drawer. It is sleeping. Or it is dead. I do not check.

-

I am fifty years old. I am a fisherman who drives a car. I am a son of the Qiantang, living in the long pause between the Ban and the next high tide.

—

The fishing ban system in the Qiantang River Basin has been implemented since 2019.

老鼠梯前大小洋

老鼠梯前大小洋,

溪中黄狗尾巴长,

莫看百尺纤来短,

一寸愁如一寸肠。

小群滩上大群滩,

多少长年缩手看,

饭甑岩高哪得上,

算来都比白沙滩。

锦水溪头溪雨多,

腊溪溪口浪生花,

石帆堪与行人便,

半日东风道下河。

横竹肩头挽巨舟,

佛头岩下回生愁,

行人眼泪声声落,

似听哀猿到峡州。

At Rat’s Ladder

Rat’s Ladder Rapids churns

gold between shores. Dog tails in the current:

fierce, and cold, and long.

Don’t speak of brief distances when for these

one hundred feet—inches are stitched

by sorrow, which is to say gut-twist grief.

Small Shoal to Great Shoal mile on grinding mile.

How many lifetimes watched

through these numbed hands all the while?

Steamer Rock dares us to climb? No chance—They’re worse

than White Sand’s slow, drowning

trance—that silt kiss swallowing our light.

Brocade Creek’s head is where rain never lifts

its needles. At Wax River’s mouth, there–

white-maned waves buck & snap like wet sheets.

Stone Sail Ridge—half a day’s wind-lifted grace,

unlocks the river’s throat with east wind’s shove—

herds us downriver into twilight’s bruise.

Bamboo poles groan–as they shoulder the hull’s

dead weight. Beneath Buddha

Head Rock, sorrow births itself anew.

Wayfarers weep–where the wild rapids roar

back like gibbons wailing through Gorge Pass

once more of memory’s raw throat.

Their echo never washes clean.

摇船

水里摇船水里歇,

水里摇船能得几个大铜钱?

六月晒得泥鳅黑,

十二月冻得紫蝴蝶。

–

水里摇船水里歇,

水里摇船能得几个大铜钱?

穿身破衣千个穷心结,

头上戴个井栏圈。

伸脚伸去到灶前,

缩脚缩在下巴前。

–

水里摇船水里歇,

水里摇船能得几个大铜钱?

绿汪汪水当褥子,

丝草蓑衣盖身体。

万台眼浪当枕头,

芦扉眼里望青天。

Rowing

A translation of 《摇船》 from 《明清民歌选》

Water bears my boat, water grants no rest.

How many copper coins for my life river-bent?

June chars loaches black and lean.

December frostbites purple butterflies.

–

Water bears my boat, water grants no rest.

How many copper coins for my life river-bent?

I wear a shirt stitched by a thousand knots of poverty,

and place a well curb on my head.

I stretch my legs, they scrape the stove

And tuck my knees, they freeze beneath my chin.

–

Water bears my boat, water grants no rest.

How many copper coins for my life river-bent?

Green water for my hard bed,

A straw-cloak shields my frame,

Ripples like ten-thousand eyes, my pillow.

Through the reeds, I watch the sky overhead.

Boatman Guild

Hangzhou

You rinsed your name in the current

and watched it dissolve–

the last letters tangled in riverweed as the rest

drifted down the channel’s muddy throat.

The oars roughen your palms to bark, their grain

running like veins, circling like tree rings. Softened

by the swelling river, silenced. The old men

call it niánlún, but you called it claimed.

You tell yourself the cold won’t climb your spine

this time, but it roots itself along your spine anyway.

It yanks your legs straight, tugs tendons

stiff as wire against bone, twisting joints into stubborn knots.

You lift your arms above your head, in prayer

or surrender–as a child, no one told you

the difference. And you sing, across translation, a new tide:

Water shakes the boat, water grants no rest.

How many copper coins for a life river-bent?

June chars the loach black as scorched earth.

December frostbites purple butterflies.

Water shakes the boat, water grants no rest.

How many copper coins for a life river-bent?

A thousand knots of poverty stitch this shirt.

You sleep rough on the dry banks, the sky leaking

through woven reeds. No tether, no anchor. You let

the river name you, knowing not to let it

near the current. Knowing it will dissolve.

舟泊桐芦

(枕流闻橹)

碧水亲依木船旁,

漫山穷苍倾入江。

枕流错闻鹅脆鸣,

清波荡出一支浆。

九二年十月十二日

Passing Tónglú

(Pillowed on Stream, I Hear an Oar)

Emerald waters nestle wooden boat’s side,

blue hills and the sky spill into the river。

Pillowed on the water, I mistake geese calling—

through clear ripples, an oar emerging.

(October 12, 1992)

春江怀古

碧波浩渺沉夕阳,

犹如金龙腾春江。

达夫药仙今何在,

观山桐居各一方。

九二年十一月

Nostalgia by Spring River

The river drowns dusk in its green sweep—

a golden dragon coils, then leaps through spring’s current.

Where is the sage & the healer who walked these shores?

One gazes towards mountains; the other dwells in a grass hut

two silhouettes facing across the river’s hum.

(November, 1992)

—

-

郁达夫(1896–1945),浙江富阳籍著名作家,以《钓台的春昼》等富春江题材作品闻名。他是坚定的抗日志士,逝世后被追认为革命烈士。

-

桐君,中国传统医学的神话人物,被尊为中药鼻祖。相传他居于浙江桐君山,所著《桐君采药录》奠定了中药配伍的基本原则。

-

Spring River is the direct English Translation of 春江 chūn jiāng

-

Yu Dafu (郁达夫, 1896–1945): a renowned Chinese writer from Fuyang, Zhejiang, known for works inspired by the Fuchun River, such as Spring Days on the Diaoyu Terrace. A prominent anti-Japanese activist, he was posthumously honored as a revolutionary martyr.

-

Tong Jun (桐君): A mythical figure revered as the father of traditional Chinese medicine, who resided on Tongjun Mountain in Zhejiang. His Tong Jun’s Materia Medica established foundational principles for herbal medicine.

.png)